8. Medals, needles and other valuables

Translated by Angela Telles-Vaz

Once, digging the clay, I found a medal of Our Lady. I was told by so-and-so to tell someone, I don’t remember his name or his face. Suddenly, I stood before him and he showed me a safety pin filled up with medals. I found them beautiful. He simply hung mine and said it belonged to him and he had lost it. Of course I didn’t believe him. There was nothing I could do.

From where did those medals come from? The one who got any would carefully keep it but inevitably they all ended up on his safety pin. He was big, had established the reputation of being the owner of the medals, and at times, showed off the collection.

I never found another one, even of an inferior saint. I thought of scouring and hiding it, to protect it from the depreciation that would bring about that fateful safety pin.

Like the medals, we owned tiny valuable mementoes, kept with an unsurpassed vigor. Even so, the objects passed from owner to owner.

I know that some had money. It was a mystery how the money turned up, similar mystery was the presence of objects that were not sent from some family members as a gift. I remember vaguely of someone older telling that he had asked a kid from the city, through the hole in the wall, to buy him cigarettes.

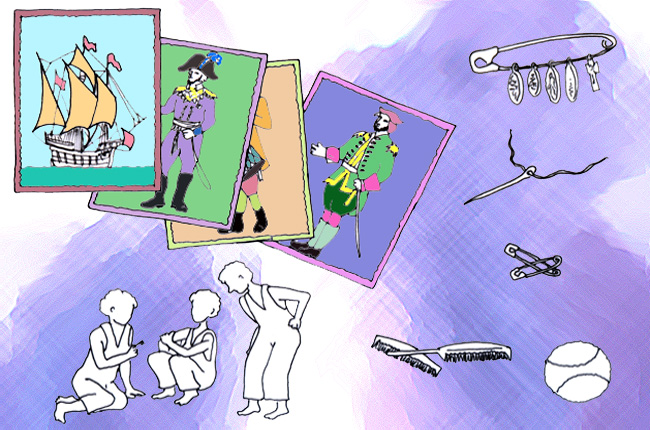

Well, the valuable mementoes consisted of combs, brushes, safety pins, string and pieces of fabric. The pieces of fabric were shredded for the threads to be used for sewing. Once, a lucky one got a bath towel, a little patch, and kept showing us that by pulling a thread from a plushy fabric, it would keep coming, coming and coming, turning into a long thread. It seemed magical. It was in fact, a valuable possession.

During one period, some had prints of the Eucalol soap. Inside the soap package there were pictures done on thick paper. What a wonderful thing! Geraldo would call me to see, I would join the older group and the owner of the pictures, would exhibit them in his own hand and no one had the right to touch them. I remember sail boats, soldiers of all periods, and there were even swordsmen! Wonderful, wonderful! They came in sets. I don’t remember the details, only the colors, unforgettable visions.

We, the small ones, never possessed anything because the object would end up by disappearing. Later, when it would to be found in the hands of a bigger one it was too late, it was so long ago that the right to claim it had already waned. If you complained, you too would be kicked in the ass.

All we could have were the needles. Ah, the needles! What patience, precision and craft! Later, I tried to make one to show Angela how they were made, when we were already living in Vila Isabel; I could only prove my clumsiness.

The major thing for the manufacturing of the needle was time. We had plenty of time. I made more than one needle. The wire appeared by one of those miracles. The wire of a variable thickness, after bending and re-bending it was cut down to size. Then its edge was sharpened with a flat stone. The next step was to find a little nail and I cry, Lord! Lord! tell me where did those little nails come from! Once the little nail was gotten, it was time to smash the other tip of the needle. It had to be pretty flat. The stone had to be a special one with no sharp end in order to not destroy the metal. Well. After been smashed, a light beat was done using the little nail on the flat tip. It was turned around and the same was done on the other side. Thus, the little nail was lightly bitten on one side and the other using accuracy, patience and calm. Usually, the head of the needle bent over and it was necessary to beat again with the cobblestone. Until, ultimately, the little eye appeared. Then I just smoothed the head of the needle on a stone in order to take the roughness out.

It was a precious jewel. We pinned it on the overall strap or front, displaying the fragile little weapon.

There were still little paper saints, pieces of colored glasses, empty match boxes, ah! all of this was essential for the locust collection.

The gifts sent by some parents were called trinkets. I said that we got one only once. My mother sent us several but we got only one. The trinkets filled with power the one awarded with the shipment. The requests were the same: comb, brush, toothpaste, soap, perfume, condensed milk and tennis ball. The tennis balls delighted me because they had two identical designs that could fit inside another, it was a miracle!

I remember that once, someone let me suck through the hole made on a can of condensed milk, Ganymede never served the true ambrosia. I also remember that an older one asked me to cup my hand. We were in a circle of contemplators and they all looked carefully at me, it was a privilege worthy of the emperor’s favorite. Geraldo watched seriously, Croesus poured a little hair lotion in my hand. Silence surrounded us. I knew it was to be used on the hair. First I wanted to smell it. However, when the hand got close to the nose, a frenzy in unison cheered and someone shouted out loud:

Not for drinking, it’s to be put on the hair!

Frightened, I trembled all over, full of shame, and wet my hair quickly with the stuff. Everyone laughed, jealous but thrilled. I hated to remember the event for a long time.

to be continued on next sunday.