15. Jorge de Souza Félix

Translated by Angela Telles-Vaz

It’s very strange to remember.

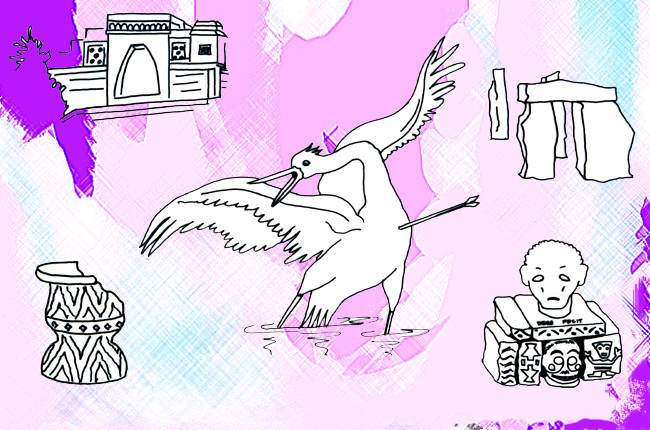

At the beginning of my attempt to penetrate in the labyrinths of my memory, images of herons and vultures emerged. The herons would be the pale memories of pleasant facts; the vultures any more frightening scene. In some moments it seems that they get mixed up.

To remember can also be as the image of a landscape in ruins. Here, a totally isolated wall, but on it very colorful frescoes of a whole scene, sharp and full of meaning. Further, a decapitated statue, would this creature be a good deity or a horrible rage? A solitary column tells me of some learning. A shattered column on the floor suggests some cause for shame.

I know well that there was a moment in my life when all of these architectural details were part of a coherent whole. It was my present time. In there, I breathed my fears and my hopes and my heart was learning slowly, little by little, the great amazement that means to live.

Years and years later, we can only manage to remember that something existed, much more in the likeness of a huge lie. And, by trying to redo the ride of the past, we discover that that city is dead.

My steps are headed to a small temple. I’m sure that I’ll find something awful. I see destroyed murals showing claws. There are scattered pieces of a broken sculpture with eyes full of pain. The basin supposed to have holy water is broken; I cannot see, therefore, a reflection of my melancholic face. It’s a pagan temple. I’d rather think it’s a pagan temple.

Some time after my arrival, a new class was introduced to us. They were put in front of us and their names read aloud, for everybody’s knowledge. For a moment I shuddered. My name was shouted, shouted in the middle of the confusion. It was all very weird. I approached Geraldo, full of astonishment and told him that I was afraid. He spoke with Antonio. The surname was not Teles. It was Félis. Jorge de Souza Félis. It should have been Félix, maybe they misread it.

Curiously, he had arrived in the company of an older brother. Geraldo looked for both of them. I don’t remember the other one’s name. Both had dark skin, almost mulattoes. Then, my namesake approached. He had deep eyes, dry skin with white spots, huge ears. He looked like the little skull of a monkey. He was skeletal, malnourished. One of his hands faced backwards by a deformed paralysis. He also had one foot facing backwards. The little cripple writhed around to walk, unbalanced and wobbly.

What a pity! What kind of suffering didn’t he go through! I cannot reconcile the act of creation having that as a result. Any god would be ashamed of such cruelty. To think about an indifferent chance, a dispassionate nature, an unpredictable destination… I still think it’s cruel.

The boy gradually approached my group. He was accepted, mingled in, but yet my friends moved quietly away. But I’m almost sure that no one made a mock of him.

One day, I don’t know why, I realized that we were playing together. Isolated from all, segregated, I don’t know if exiled under the pressure of others, for fear or by his own volition, the little crippled clung to the only lifeline he found: someone with a name almost identical to his. It was as if I were condemned to accept him because I had such a name.

I don’t know about our first games. What has marked me profoundly was that I got frightened when I found out that our friendship wasn’t similar to what we had with the others. I ordered and he obeyed. Humbly, he asked me what to do. I ordered with anger. He looked at me with eyes full of horror and I have the impression that I used to beat him. I’m not sure about that. He was a little slave, submissive, morbidly docile and desperately obedient. It bothered me a lot that he didn’t react, that he accepted my injuries and continued to sniff for my company. I redoubled my wickedness, tearing up his cards, destroying his toys.

He returned like an unwanted dog, looking at me with those eyes that I only recognized when I saw once more in the documents of the Nazi concentration camps. I exaggerate for sure. My regret filled with terror must, now, be adding Expressionists brushstrokes to this shredded memory.

I don’t know what bothered me most: the fact that he was a cripple, not giving me the opportunity to abandon him; or if by the growing regrets that my actions created later in me. I returned to him prepared to finish it all, I beat him, he would keep himself a little far from me, head down and then, full of pity I would decide to talk to him. However, I would not admit any mistake, I scolded, I swore, I felt as his owner.

I don’t recall how it all ended. I think the other boys returned and he left quietly, I don’t know. I don’t see him playing with me anymore, after that dark time. Maybe he joined an unhappier group, the pissers, who knows?, being received as an equal. For there, happiness had reached the minimum limit. At ground zero, it wouldn’t matter one crippled more or one crippled less.

The last memory of that unfortunate creature comes to me as if I were seeing a bloody bird on a mosaic full of soot.

On the eve of my departure, one day so far like any other day, we were gathered for the reading of the names of those that were going to “leave” the school. Geraldo was called. When the next name was heard, I didn’t get it right, I was sure they read Félix. They started pushing me out of the line, it’s not me, it’s him, he walked out awkwardly, they pulled him, pushed him, I returned to my seat, Geraldo took me out of the line and the crippled boy stopped, faltering, looking at me with his huge eyes deep inside those eye sockets.

I don’t recall the rest.

No… I don’t recall the rest…

I think the intense and complex feeling that followed, erased that boy from that scene. Much later, recalling the fact was when I suffered for him.

Poor boy, poor crippled boy, whom unfortunately, at least at that moment, poor the one who wasn’t me.

to be continued on next sunday.