12. Two supervisors and a priest

Translated by Angela Telles-Vaz

Some characters must be brought into play in this tapestry that resembles almost like lacework. It seems the threads look loosen up without them. Or it’s as if from now on, I insert needles to make big stitches, to tack the gaps and patch the holes. Although they are active and important needles, they are also threads, stitches, nodes and bows that tight to give form to increase the fabric texture.

Or bows that are tight.

If I think now about the supervisors and the priest as puppeteers that owned our unarmed will, in order to relieve them, I try to imagine them as puppets moved by superior hands. In this case, puffy hands of an old, huge and ugly whore, like some bitches of Fellini, this huge and dirty slut they call human society.

I was never able to solve the mystery I had inside of me about the supervisors. They were two. Right. Antonio and Sinuca. I have vivid memories in which both of them participated. Always separately, except during the time of the purging. The mystery rooted inside is: which one came first, which one came later? I think, at the beginning it was Antonio and then Sinuca. But I do get mixed up trying to remember what happened in the end, a little before departure, when I realize that it’s Antonio who is there again. For instance, the Nights of Paddles. It’s very likely that they both worked together, taking turns.

I don’t know if this is the case. I don’t know if this is the point. Everything is very blurred, very hazy and very white. Would it be worth to try to interpreter it all?

Well, well, well…

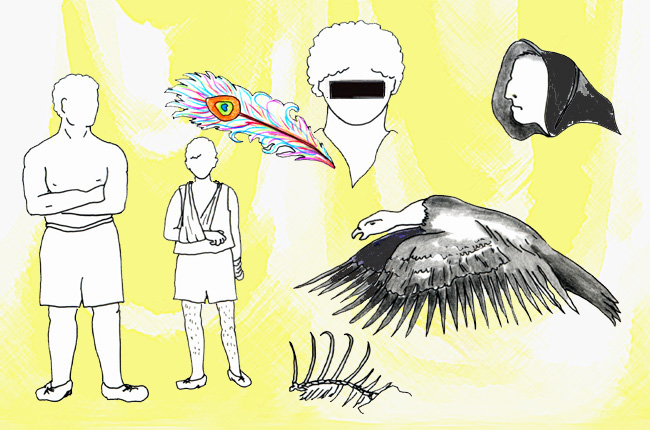

It was Antonio who accompanied us on our way. He was on the train together with Aluísio. Antonio was a huge and very strong mulatto. He had short, kinky hair. He was hated by everyone but if I try to remember of one only moment that I felt any negative feelings towards him, I can’t. Of course I felt the general feeling, the feeling of a deer being delivered to the lions, but not the silent hatred feeling of all the other boys, the silent rebellion of all the students.

In fact, my feelings were dubious, like a child and his father. He liked me very much, protected me openly as all the big boys did. So, I liked him but also feared him. The conflict should be worse for all the others. They were hardly beaten and yet he showed many times an extremely nice attitude. There was, for instance, a lot of camaraderie in the old boy’s dorm. He slept in the lower bunk bed and they talked up until late. I wonder though, did he actually sleep there? Or just stayed up talking until falling asleep? I remember his conversations, telling ghost stories. Another thing: did he have sheets? a blanket? Because at the end, when the mattresses became thin and full of holes and were used as covers, even the older ones didn’t have covers themselves. Geraldo and I needed to sleep on the same side of the bed, curled up tight in order to pull the bottom of the mattress over our bodies. Who knows if Antonio slept in some other accommodation? Or was he himself another victim of the general misery?

I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know, no.

I don’t remember

Fate was cruel to Sinuca. He was the other supervisor. I think he never laid hands on me. But I don’t feel for this creature anything nice, nothing edifying, but a sentiment mixed of a caged hatred and an incapable pity. He was from the Northeastern region. Thin lips, malicious eyes, curly hair glued to the skull. Tiny and skinny like a hungry rat. Perhaps that’s why he was so aggressive. Antonio was huge. He would arrive with confidence. Sinuca would come in his shorts, swinging, balancing over his two slender hairy legs, he needed to shout louder and kick. He knew how to be nasty, I cannot think of anything less unpleasant about this person. Was it because he never gave me any attention at all? Or because he simply was regarded by all as a wild beast and consequently fear and hate from them all infected me? Perhaps it was all of it together. He was mortally hated. Some time before my departure, he was violently beaten by some of the older students. Hate had risen as pressure, anger increased and the despair angered those troubled hearts and they caught him off guard. They drove him into a dark corner and rushed themselves at him, discharging at the executioner the fury of a thousand victims, transforming each of the aggressors in attorneys of a collective rage.

I think this is the part that I restrained myself, scared, and repeated full of grief the reading of a passage from the book, The Tenement, from Aluísio de Azevedo, in which Jerônimo and some black guys beat up Firmo to death. A word never left my mind: the bloody package.

Sinuca disappeared completely and then came back as soft as a feather, smooth and nice. He was limping. He was patched as the Tortoise, the land turtle from the fable, who tried to travel to the party in heaven. The Tortoise entered inside the Vulture’s guitar and enjoyed the party. When they returned, the vulture found that out, turned the guitar over and the Tortoise fell off. That’s why he has cracks on his shell. That’s how Sinuca was, the patched one.

Trips to heaven can transform ascension into fall. This is a foolish, awkward and unnecessary remark.

Navigating among the students and the gods of the Olympus, who were the supervisors, floated some special students, with some blatant regalia. Were they the messengers between the worms and the authority?, like Mercury. Or bed waiters?, like Ganymede. I don’t know if they were many, these live purgatories, that were not only the gnashing of teeth of cold endless nights, nor achieved to be the transitory bliss of absolute power. At the top, they were used in secret, to avoid the disgrace known by all. At the bottom, they were scorned as the crow who adorned itself with the peacock feathers. It is true that I only remember one of those pitiable creatures, not a crow anymore and yet not a peacock: Aluísio. I say pitiful, for he was badly regarded among the students; for nothing more. I was too little to understand these complexities.

No more fables or mythology. I don’t want any literature over HIM. I’ll try to restrict to the scalpel of my memory. Perhaps my hand will tremble as I write. I don’t want to be cruel and yet I can’t be soft.

Next to the Orphanage lived the priest who was our Principal.

From where does such nauseate feeling come that the memory of that priest brings to the surface of the lost waters of my soul? He was the boss, the absolute master. If the correction paddle hurt, it was he who gave the order. If the food got worse, some frog or lizard must have been spewed from his mouth along with his coward orders. We all knew that he was the chief-puppeteer who held the strings that made Antonio and Sinuca’s movements. We all knew. So much so, that on the terrible Afternoon Rebellion, it was towards his home that the courageous and determined cries were blasted.

Bucket had no name. Friends don’t need a name. Neither that man had a name. He was just The Priest. For me, a kind of King-Vulture, a dark stain that came and went as he pleased. In my memory, he never walks with his feet on the ground he just comes and goes, floating like a ghost.

It seems that during my stay in his circle of hell, that poor Mephistopheles was mentioned in one of Rio’s magazines or some newspaper. I don’t know the proportion of the scandal. My grandmother used to say that he received the gifts from family members but didn’t pass them on to the students. My mother mentioned pairs of shoes, and clothes that weren’t ever seen by any of us. It was this article that caused my family’s despair and led them to commit themselves to get the money for our return.

Besides a hazed shadow in black gliding (oh! that Teutonic monk from the movie Alexander Nevsky), this creature fortunately didn’t mark my soul. I don’t remember his face, and know nothing about his eyes. It’s just a Vulture with broken wings forever pacing inside of me. It’s an inconvenient fly that comes back if I send it away.

For the flies of memory, there’s no insecticide.

Fortunately, he visited us very seldom. He could have come limping, in patches, with a wrinkle of concern, with sadness in his eyes, and yet any of these tiny human miseries could have been enough to mark the rest of my life. I would feel sorry for him and suffer with him, willing to find an excuse, pretending to forgive his major and only crime, which is, according to Spinoza, of ignorance. The person who agrees with Spinoza is led to forgive easily.

Years later, I’ll think: the guilt of human sin, Mr. Spinoza, it doesn’t derive from ignorance but from the neurotic immaturity of the human soul. Just a decent social life will enable human relationships to mature.

But I did not know Spinoza, I was seven-eight years old, a little more, a little less. My mind of today doesn’t have the right to philosophize on behalf of my previous fate. I was seven-eight years old but wasn’t Existentially incapable. If I could suffer, I could hate. The pain is gone, yes, but it didn’t turn into a zero inside of me.

I don’t give anyone the right to forgive in my name. I don’t give to whom I am today the right to act on behalf of who I was.

Today, I know that I cannot condemn him. But the boy that I was has already delivered him to damnation.

I don’t delete what I thought at that time.

Nothing, I repeat.

I’m only remembering unpleasant things that have already gone.

I wouldn’t like to see that man again.

to be continued on next sunday.