4. Ankoraŭ la loĝantaro

Mi sidadis surgrunde, meze de kelkaj knaboj, eble mia unua aŭ dua tago, iu alvokis:

Vazego!

Vazego alproksimiĝis kaj ekrigardis min. La moknomo estis tro stranga. Mi ekridis.

Ĉu Vazego?, mi demandis.

Jes.

Ĉu Vazego de merdo?, daŭre ridante. Mi ne scias el kie venis tiu ideo.

Vazego de merdo estas pugnobato meze de viaj kornoj.

Li koleriĝis kaj mi tute kuntiriĝis, honteme kaj malkuraĝe. Estis nova situacio, mi ne deziris alfronti ĝin. Iu pli agresema reago terurigis min, mi ne ŝatis disputi. Pro tio, honto kaj malkuraĝo. Mi ankaŭ pentis, kiam mi rimarkis la ofendon.

Tamen, nenio okazis. Li iomete grumblis, min rigardante per kolero kaj ĉagreno kaj ĉi tie stumblas mia memoro. Post tiu okazaĵo, ni estis amikoj porĉiame, de ĉio ni kune partoprenas, ĉiuj duonklaraj memoraĵoj montras al mi peceton de li.

Vazego. Ĉu ankoraŭ vivas la viro kiu, en perditaj tagoj de mia infanaĝo tenis la ŝarĝon de tiu moknomo? Kia magra donaco de la destino! ĉar eĉ nometo ne restis al li! Povus esti ordinara nomo kiel Francisko, Paŭlo, Jozefo. Povus esti minimume karesaj moknomoj, Ŝiko, Ze, Mane’! Ne. Vazego. Vazego kaj nenio pli. Estu li, do, Vazego, ĝis la fino de miaj rememoroj.

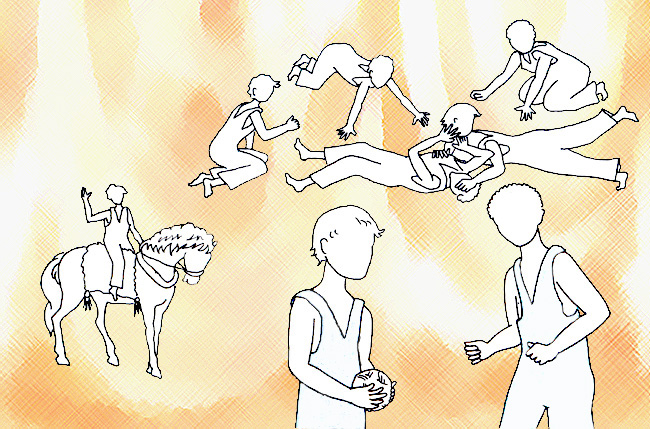

Li estis mulato, mulateca. La plej forta trajto de lia vizaĝo estis la makzeloj kiuj iris antaŭen, kvazaŭ la dentoj intencis alveni pli frue. Mi ne memoras pri lia temperamento. Mi nur pensas pri la fideleco de lia ĉeesto. En la rojo, en la kamparo, kun la argilo aŭ kun la pilko, Vazego estas kune. Nek amara nek milda; nek ridas nek ploras; nek estas facilanima kiel Valdemaro nek melankolia kiel Hermeso. Estas la kamarado.

La lasta amiketo, ene de tiuj duonviŝantaj rememoroj, nomiĝis Ze da Silva. Denove, ironio. La antaŭa estas sennoma, tiu ĉi havas nomon kaj familinomon, sed nomo kaj familinomo kiu apartenas al neniu. Joze da Silva, en Brazilo, estas la plej ofta nomo. Ĉu liaj dentoj estis troege blankaj?, aŭ ili aspektis troege blankaj pro la frapanta kontrasto kun sia absoluta nigreco? Ĉu li ridadis la tutan tempon?, aŭ simple okazis ke la absoluta blankeco de liaj dentoj pli forte legitimis lian ridadon? Mi ne scias. Por mi, tiu ridanta nigruleto porĉiame havos la plej belajn dentojn en la tuta mondo. Li posedis fajrecan energion, li saltas pli ol la cetero, li ludas pli ol la cetero, li moviĝadas pli ol la cetero, elektra formiketo.

Mi ne kapablas imagi lin malĝoja, en tiu nuno nun rememorata aŭ en sia apenaŭ imagata estonto. Valdemaro, pli malfrue, certe montrus duonkaŝitan doloron en siaj helaj okuloj, Hermeso plorus, Vazego aspektis rompiĝema, li facile tremadus. Ze da Silva, ne. Tute certe, la nigruleto ĉiam montros tiun enorman kaj blankan rideton, spontanea eĥo de la respondo donata de la afrikana argilo al la nigra diaĵo, en la tago de la kreado. Facile estas imagi lin kiel feliĉa dancisto en samba parado en la karnavalo de Rio-de-Ĵanejro. Eblas pensi lin amorante la plej belan nigrulinon, efemera miksaĵo inter du poreternaj noktoj.

Mi bezonus strebi por elpensi lin surgrunde, iel ajn falante meze de kotaro, sangplena, truita de la kugloj de Justico. Lia ridado ne ĵetis lumon sur tiun vojon. Tamen, mi scias ke ankaŭ tiu pado estas ebla.

Mi indikis du aliajn nomojn, Blanka Katino kaj Marketo. La ĉeesto de tiuj du homoj estas stranga. Ili restis en mia memoro danke al du incidentoj okazintaj dum mia ĉeesto en la internulejo. Ili tute ne ekzistas antaŭe aŭ poste, nur dum tiuj du rapidaj kaj neforgeseblaj momentoj.

Blanka Katino estis blonda blankuleto; blanka kiel lakto, blonda kiel fadenaĵo de maiza spiko. Lia voĉo estis akuta kaj ĉiu frazo ridigis la internulojn, ĉar lia akcento estis de la regiono, tre malsimila al tiu de la ĉefurbo. Ŝajne li havis pli aĝan fraton tiel blanka kiel li, aŭ eĉ pli. Du blankaj paperfolioj, inter grizuloj, kupruloj, bronzuloj, purpuruloj, rozuloj kaj nigruloj. Ili estis sinkaŝemaj kaj timemaj, aspektis kiel bestoj en danĝero.

Iutage, mi luktis kontraŭ Blanka Katino. Mi ne scias pri kialo. La rememoro komencas kiam niaj korpoj jam interkroĉiĝas. Mi ne scias ĉu tio daŭris, ĉu ne. Mi scias ke li ungegis mian tutan vizaĝon kaj la gratvundoj longe ardis. Ĉu pro tio li ricevis la moknomon? Ĉu eble li jam luktis per ungoj antaŭe? Ankaŭ pri tio mi ne memoras. Mi certe ripetos tion, mi ne memoras, mi ne scias, tio forviŝiĝis ene de mi, la suno de miaj matenoj ankoraŭ ne ĵetadis lumon sur mian tutan vivsperton kaj nur la plej neforgeseblaj momentoj lasis siajn spurojn; eĉ tiuj, svagaj kaj fuĝemaj. Tio ne tuŝas la aferon.

La emocio post la lukto estis pli forta ol la lukto mem. Mi memoras pri la morala doloro ĉar mi vundis lin. Mi neniam luktis, tiu estis la ununura fojo dum tiuj dudek monatoj. Mi timadis, mi estis humila, milda, malkuraĝa, ĉio kune. Sed, precipe, mi bedaŭris agreson, kontuzon. La gratvundoj sur mia vizaĝo proponis al mi specon de konsolo ĉar mi sciis ke ne nur mi ofendis sed ankaŭ estis ofendata.

Marketo estis malgrandeta. Blanka, blonda, figuro inda de tiuj sanktuletoj en katolikaj kartoj. Laŭ mia memoro, li estis tre antipatia. Liaj dentoj, male al tiuj de Vazego, estis internen kaj li afekte lispis dum parolado. Tio tre nervozigis min. Probable nur instinkta kaj primitiva envio ĉar ankaŭ li estis protektata de la plejaĝuloj. Mi memoras ke li subite maldikiĝis kaj malaperis. Li estas en la domo de la pastro, iu diris, pro ftizo. Iam, iu rakontis ke vidis lin de supre la muro, li promenadis surĉevale; la diraĵo plenigis min je malkontento. Ni paroladis pri la bona manĝo, kiun li certe ricevadis. Ĉirkaŭ lia bedaŭrinda foresto, ni teksadis paradizojn plenajn je lankovriloj, sukeraĵoj, promenadoj kaj makaronio. Kelka tempo poste, li aperis. La koloro revenis, li iomete dikiĝis, ne plu tiu skeleteto minacante fali pro iu ajn forta vento. Mi ne scias el kie venas tiu impreso, sed post la reveno li ŝajnis pli simpatia, la rideto estis pli amikema, la parolo estis pli spontanea. Malgraŭ tiu plaĉa bildo, li ne partoprenas en niaj ludoj, ne apartenas al la grupo, ne plu aperas en rememoroj.

Aliaj nomoj plektras la kordojn de la harpo de miaj memoraĵoj. Sed mi iomete lacas pri homoj. Nunmomente. Poste, mi revenos al ili. Mi bezonas atmosferon, spacon, mi volas denove revivi la memoraĵojn de tiuj tagoj. Mi trapreĝos la rozarion de la travivaĵoj de mi memorataj, mi volas grundon, mi volas instruojn, mi volas nokton por dormi, mi volas manĝon. Tiu mia bando de fantometoj aspiras al bano en la rojo, al ŝoto sur pilkoj, al skribo de leteroj, kion mi scias pri tio? Pro tio, mi priskribos la scenejon de la tragedio, tiu batalkampo de maljustaj luktoj inter tre malegalaj fortoj.

daŭrigo en la venonta dimanĉo.