10. The letters

Translated by Angela Telles-Vaz

Campo do Meio, so and so.

Mom, or

Auntie, or

Dear Parents:

Greetings

Firstly, I wish you all health and happiness.

Secondly, I would like that you send me as a gift:

a comb;

a toothbrush;

toothpaste;

if possible, Eucalol soap;

a tennis ball;

a pair of shoes;

a sweater;

a bathing suit;

cans of condensed milk;

cans of milk candy;

and this and that,

and this and that.

All our letters were hopelessly the same. The same introduction, Greetings, firstly, et cetera, and the list of requests as followed. Here there was a little variation in size. The prodigal stretched the snake and asked non-stop, accomplishing themselves before the party, enjoying the pleasures that written words brought to their taste and body. Others, more timid, limited to the barest essentials.

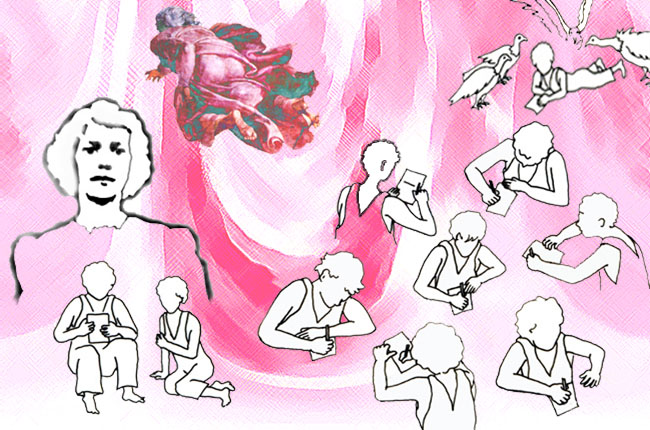

The letters were written in the classroom. Scrap paper first. I’ve got the feeling that it took us one week to write these letters. The handwriting was examined, the content criticized. We would return to the desk to redo this or that, recopying everything in another draft. Someone had said that it was forbidden to complain? Or that the unanimous and coward silence was one of those typical attitudes of the weak?, isolated by the authority. Who would dare to rebel against that tyrannical Olympus, we the helpless, the starving, the weak by the lack of vitamins, paralyzed by the cold, and above all, soaked and impregnated by the most deadly fear. There wouldn’t be an efficient Prometheus to provide aid to that bunch of nostalgic victims of pilgrimage.

In Nazi concentration camps, Russian and English, and in all of the others, it must have been and be worse than there. But those scapegoat pups had not, in most cases, entered pre-puberty. We paid the sin of living.

Today, I have no idea of the magnitude of my suffering. I try to evaluate it through pieces of my memory, trying to understand melancholic memories, painful memories. Nevertheless, I give neither myself nor anyone the right to forgive.

I diverted myself from the purpose of the chapter. The subject been discussed were the letters. Greetings, I wish they had sent me the list and some beautiful and pleasant best regards, where each Pangloss, bastard of the paddle repeated without conviction that we were in the best of possible worlds.

With the draft approved, a wonderful sheet of white paper was given to us, white, white as milk, as a lily, there was nothing more pure in the universe. On the header, a drawing of the building probably written by some fairy or an angel: Saint Joseph’s Technical & Agricultural Institute. Then the tiny frightened letter sled transforming the paper into a living organism, with a far request, a concealed request for help, wishing that, when the letter was mailed, the real message would be understood, suspicion would arise, what was not written would be understood, that something would be sensed!

How many of these letters were sent? I cannot know. My mother, grandmother or older sister, may have remembered. They no longer live. The others were young at the time and were beginning the battle against the humongous city. Maybe they paid no attention to the situation. I make this remark because I got the impression that the letters, or almost all of them, were eventually torn apart. That was basically classroom work, calligraphy, benevolent illusions, granted by the owners of our unessential, useless and worthless little lives.

Once, the supervisor came into the classroom and said that the previous letters contained too many requests. People would think we had nothing. The requests should be restricted to the objects considered luxury like tennis balls and toys. Since then, the lists were reduced, the snakes shrank frightened and it was taken from us the possibility of feeling indirectly pleasure, of being happy writing words, listing pieces of comfort, those little fantasies full of enchantment.

It was worse than that for the students that had nobody to write to, the children of nobody, the half retarded or the confused litter of mice whose mothers were rambling around the world, sniffing for coins and rotten food. The teacher demanded from one of them, I think, to pretend he had a relative that would attend to his request. I do not know from where I got this conviction, but I’m certain that he could not have had the courage to write “dad” or “mom”. It would be going too far with this worm dream. He possibly invented an uncle, an older cousin, a distant godfather. Not a father. Not a mother.

It must have been little humble and meager words, like the one who made them alive. Ragged little words, barefoot little words, with cracked lips and eyes full of gummy secretion. Worn, discolored, eventually turning into tuberculosis, sobbing, spewing out bloody phlegm little words. The message would end up as the owner, dust in dust, without reaching any country, without being worthy of a sloppy reading, without having had the brilliant destination of filling with tears a distant heart.

How ashamed would Jehovah feel, he who writes letters of fire, how ashamed would he feel if he had bothered to read those little letters?

I give him no right to ask for forgiveness.

Letters were also received.

Abraim should be for sure, an African prince. Even knowing that he was the first in alphabetical order, it charmed me the fact that his name was always shouted. He became lit in the midst of sullen and heavy birds, like idiot vultures, to hear from their lip most moving preaching than the one of the monk of Assisi. He read and reread full of contentment, until the group pleased and half agonizing would brake off.

I would have liked to know the goddess who gave birth to that prince. In my memories, he was as beautiful as a statue, in my mind he arises beautiful as a statue. It’s true that he was first in line for the purges, but for sure the high price was worth it. Someone from afar, accompany him. I do not know on what grounds he got there. It does not matter. Or would it matter? The important thing is to know that someone was following him from afar, consoling him, lighting up the darkness of the pit of doom that had imprisoned him.

Geraldo and I also received letters. I remember one that Geraldo told me about that brought sad news: his godfather Antero and our uncle Doque both had passed away. The only thing I knew about godfather Antero is that he had a wonderful farm where Geraldo spent some holidays. There, one would eat polenta and drink milk. About uncle Doque, my grandmother’s brother, I can only write that he reminds me of okra. Would he have liked to eat okra? Would he drool like an okra? How could I find out? At that time, the two deaths meant nothing to me. It was about a man that I hardly knew and a converted protestant uncle, crouched in a corner of the kitchen with the hymn book in his hands, making up the lyrics for the hymns he didn’t know. But this is a detail heard much later from my aunt Natália.

What embraces me when I remember the letters is a kind of floating picture of my sister Maria da Glória. I don’t know if she was the one who wrote, if it was she who wrote us the letter about the two deaths. Suddenly, her smiling and sad image would appear and I felt a unfamiliar warmth and heard old songs, like the ones we sang in the deaf and dumb streets of Manhuaçu, and it was as if my guardian angel went away leaving her caring for my emotions.

I felt nostalgia!

to be continued on next sunday.