2. The trip

Translated by Angela Telles-Vaz

Proofread by Izabel Arocha

There was much light around us. It seemed that we were in a glass palace. I don’t know how we got there because I’m already sitting inside the train. Geraldo is next to me. I see through the window that outside, my mother cries. Aunt Ananísia sticks her face through the window and asks:

Who will care for them?

Aluísio will.

Who?

He is that one over there; someone pointed to a burly lad, quite fat, fair skin, curly hair, I would later remember, like the statues of the god Apollo. I would also always remember him later when hearing the word puffy.

Lad, are you going to watch them?

Yes ma’am!

Care for them, Aluísio, for God’s sake! Care for them. Don’t let anyone mess with them, no! And she kept pointing at me and Geraldo.

My mother cried louder and Geraldo also began to sob. I didn’t understand how it was possible to cry in a place so beautiful, with so much light!, I’m inside the train!, my first trip!

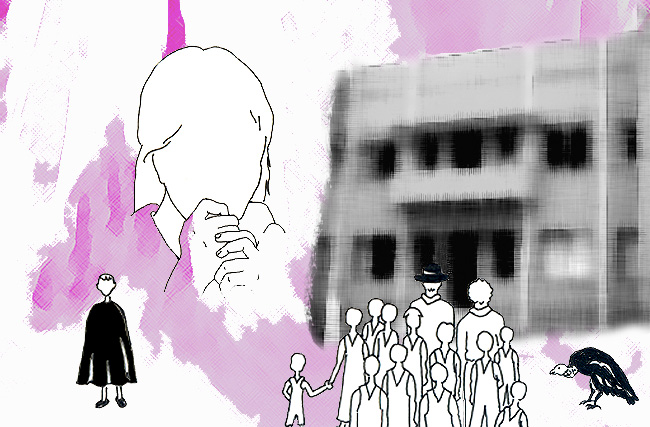

The fact is that the trip was more fascinating then all the rest. I wore my little black cloak, vintage type, involving the whole body, sleeveless, the arms loose inside. I was looking forward to the first motion.

As I write now, I remember that Antonio, the supervisor, was also there. He was a huge mulatto with fair skin. He had a hat. I just remember that detail because during a stop he fills the hat with guavas and runs to catch the train already in motion. It was him that just told something and we all sat silent and my aunt repeats her request to Aluísio,

lad, you’re going to be responsible, lad, we rely on you, lad,

my mother is in despair, I hear a thud, everything starts shaking, and instead of the train moving forward, they are the ones that are slipping back: the aunt, the mother and the others, faster and faster, until there’s complete darkness outside.

Geraldo cries. Does anyone else cry? I do not recall. Myself, Geraldo, supervisor Antonio and the lad that had received the recommendations of the aunt: Aluísio. On the trip we learned more. He was a resident of the orphanage were we’re going to, but helped the supervisor, bringing and taking the students back. I don’t know if it was during the trip or after that I heard:

Aluísio is Antonio’s wife.

My comprehension did not reach the subtleties of the sentence. I am well aware of my comprehension of the fact at the time: they slept together, they were married. And “sleeping together” I just understood it as sleeping together. Nothing else mattered. I did not know that you had to be a woman to be the wife of John Doe. That I had no other way but accept the truth, keep it, I might need it another time. But why all the giggles when they repeated the sentence?

Some time after the beginning of the trip, I discovered a truth that filled me with joy. If I looked out the window, while the train moved, everything was going backwards but it was the train that moved. However, if I looked at the floor of the train, it seemed to stop and only shake. No, it didn’t stop, that was the wonderful truth. It seemed to stop but it moved. I remained like that for a long time, focused on thinking that it seemed to stop, that everything seemed to stop, if I kept looking at the floor.

And here I am, already in a truck. We are all crowded inside the back of the truck, it’s already night. Years later, Geraldo remembered that we went from Rio to Cruzeiro, in the State of São Paulo. From there, we took another train, to a station that had another name besides João, João-I-don’t-remember-of-what. After some time, we took the truck to Campo do Meio. I don’t know about that, there are no such details within me. From Brazil’s Central Station train, one powerful engine, I see myself on the truck. A lot of people now, all piled up, it’s dark, they speak, move, I cover myself with my cloak.

Now, we are walking towards the house. It’s already night, I go hand in hand with Geraldo. Suddenly I realize I’m without my cloak. He warns me that nothing can be done, the truck has left already. The cloak is gone/disappeared. It was black, it was warm, it was a piece of my hometown Manhuaçu, that accompanied me and it was a constant and vivid reminder of the sad look of my mother who had made it for me when I started going to school.

So, at some point, we entered that house. This moment is also completely erased from my memory. But inevitably we entered. Yes, of course we entered, because my heart will not ever forget the handful of memories that drew inside me. Some memories are white and off, like herons that fly in the fog; others are vivid, sharp, have smell and volume, like a fierce vulture, with its sharp claws, or its ruthless beak, bloodthirsty…

to be continued on next sunday.